Recently I was in a used bookstore, checking out the politics section, when I happened upon Jason Stanley’s How Fascism Works. Stanley is only known to me because of his regular and strange Twitter blow-ups, but I was curious if there was an intellectual depth present in his book that cannot be captured in 240 characters. I flipped the book open to chapter two, titled ‘Propaganda’, which begins

“It’s hard to advance a policy that will harm a large group of people in straightforward terms. The role of political propaganda is to conceal politicians’ or political movements’ clearly problematic goals by masking them with ideals that are widely accepted. A dangerous, destabilizing war for power becomes a war whose aim is stability, or a war whose aim is freedom. Political propaganda uses the language of virtuous ideals to unite people behind otherwise objectionable ends.”

I often see definitions of propaganda that take this route, but I have to admit I expected Stanley to have a more nuanced view of propaganda, particularly one that reflects how propaganda operated in Nazi Germany. In his book How Propaganda Works,1 Stanley says that propaganda is his name for “political rhetoric”. Rhetoric is typically described as the art of persuasion, and for Stanley propaganda is political rhetoric which tricks people to adopt a flawed ideology which they would not normally accept. But this description misses the true essence of propaganda. A person under the sway of propaganda does not need to be tricked via persuasive, calculated rhetoric; a person under the sway of propaganda is incapable of thought, and so does not need to be persuaded at all.

When you say “Nazi propaganda film” most people think of Triumph of the Will, which uses footage from the Reich Party Congress to depict them as an ascendant power, capable of achieving their goals. But that’s not what all Nazi propaganda was like. Consider Kolberg, the final propaganda film produced by the Nazis. Kolberg is a costume drama about the siege against Kolberg during the Napoleonic Wars. Now, you might be thinking ‘what does this story have to do with Nazis?’ You open up the Wikipedia link I provided and scan the page, searching for an angle. ‘Oh, the story is about heroic resistance!’ ‘The story exemplifies the need for a strong leader, obviously.’ To me, the answer is it has very little to do with Nazi ideology, and much like most Nazi propaganda its goal was not to convince people to adopt the Nazi’s delusions of grandeur, but to use fantastic storytelling elements to lull the viewer into a state absent of thought.2

Hannah Arendt recognised this clearly in Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi who oversaw the deportation of Jews during the Holocaust, whose trial Arendt covered, leading her to coin the term ‘the banality of evil’. Amos Elon claims Arendt saw that “Evil comes from a failure to think”. George Orwell perceived this as well. In 1984, Orwell’s brilliance shines through because he not only shows that totalitarianism must police people’s thoughts, but must go farther, destroying thought’s very foundation. Doublespeak strips language of its ability to convey meaning. When old newspaper articles are memory holed, the public loses its collective memory. When the party declares that Oceania has always been at war with Eastasia, they are ensuring people are not using their own memories. Without memory and meaning, original, deep thought is not possible.

The historian Christopher Lasch once wrote that “Propaganda seeks to create in the public a chronic sense of crisis”. In a crisis, there is no time for thought, only action, and when the crisis is chronic, there is never a chance for thought.

In this sense, it is not surprising that Jason Stanley, a man who simply cannot log-off Twitter during a spat,3 fails to stress this aspect of propaganda. Twitter is a site defined by its chronic sense of crisis, with the day’s issue taking on cosmic importance before being bombholed as quickly as it arose. The crisis changes and no one revisits their own proclamations of doom that failed to come to pass. One’s enemies’ mistakes are screenshotted, ready to deploy paired with “this you?” next time they Tweet, but one’s own mistakes are given far less thought. Barely any memory upon which to learn from one’s mistakes.

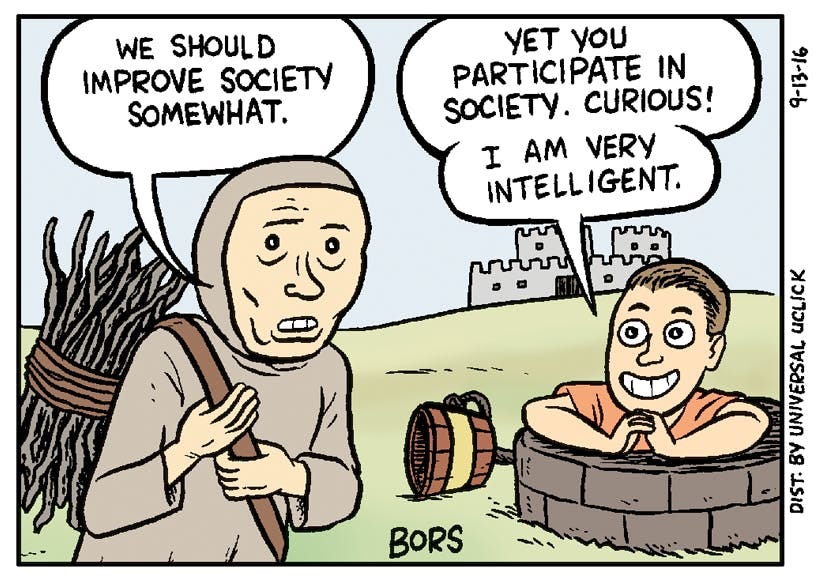

Worse than that, people on social media have pre-canned responses to whatever intellectual challenge they face. Someone accuses you of hypocrisy? Just paste this Matt Bors comic in the replies

Someone asks you to justify your claims with some evidence? Just say they are sea lioning4 and post this comic

When people don’t like something, they don’t articulate why, they just say “it’s not a good look”, expressing disapproval without actually articulating that disapproval, because doing so would involve thinking, rather than mere reaction.

Regular readers and friends of mine will know that I am dismissive of the narrative that Russian trolls making Facebook memes were responsible for Trump’s election in 2016, but I do think social media deserve some of the blame for the sorry state of what passes for political discourse these days. At best, social media has laid bare the strategies we use to lobotomize ourselves and protect ourselves from ever having to think, but at worst it has put them on display in a fashion that invites people to copy them, rather than reject them as the shallow coping mechanisms they clearly are.

News sites have followed suit, employing their own strategies to keep their consumers from thinking. The New York Times attaches the term ‘far-right’ to whatever it wants you to hate, in order to make sure you know to fear it before you even know what it is. Alternative media is often no better. Alex Jones seems like he’s in such a constant state of crisis that listening to him yell, one cannot help but wonder how he doesn’t spontaneously explode. Both strategies serve not to help the consumer think about world more deeply, but rather enable them to stop thinking about what is going on at all.

Propaganda succeeds when it destroys people’s ability to think. Our governments don’t need propaganda film departments because we aren’t thinking at all anyways.

His book titles seem to follow a formula, I’m a little surprised he didn’t go with ‘Propaganda for Dummies’ or ‘How Fascism Works: A Guide’ though.

In Weimar Germany, the Nazis and Communists would often go after the same people for recruitment, suggesting their targets were not people devoted to right-wing politics but people in search of extreme politics.

Kudos to Stanley, it seems since I wrote this article he has managed to kick his Twitter habit.

I’ve always thought this comic/response is weird because the sea lion seems to be correct here. If I said ‘I don’t mind most religions but those Christians I could do without’ I don’t think a Christian over-hearing that would be in the wrong to ask me why I made that hateful statement.

I love this subject. Our brains are so fascinating.

True that propaganda is intended to get people to take action, whether it's selling cars or wars. Related to that, it's easier to train a smart dog than a dumb one.

Intelligent people are moved to act without thought. Something about the poster, film, bumper sticker, political slogan, lyric, etc. compels them. Lower IQ people will follow the crowd, but they're not moved by the propaganda itself in the way that higher IQ people are.

Very insightful. I would add one point. Propaganda fills the void that should be filled with thought. The propagandized need ready-made opinions, which they can present in lieu of their own thoughts. That’s why challenging those opinion appears to them to be a personal attack -- violence.